World War I witnessed the first tanks and the first steps toward restoring movement to a firepower-drenched Western Front stalemate that devoured men and materiel to shove an enemy back or hold the line. We have witnessed the first steps in a battle in the Winter War of 2022 near Lyptsi toward the equipment and tactics that could restore movement to the stalemated integrated strike complex warfare that links persistent surveillance with timely precision fires.

In fact, this one was the first attack of its kind: a successful, all-drone assault on Russian positions. The assault, deserving of a place in the history books, took place near Lyptsi, in the Kharkiv region of northeastern Ukraine.

It was a test – initially expected to fail – of whether multiple units could orchestrate a mission with dozens of FPV, recon, turret-mounted, and kamikaze drones all working in tandem on the ground and in the air.

Ukraine’s Ground Unmanned Robotics Unit was given a mission:

The units involved in this assault were tasked by the Khartiia Brigade commander with an experiment: could they organize an all-drone assault within a week – and actually pull it off?

But the assets were unknown territory, as the ground drone unit commander explained:

“When we felt discomfort, we developed. We did not [previously have expertise in] drones, it was uncomfortable for us,” ‘Happy’ explained. “And it forced us to work more intensively on ourselves and with drones.”

The unit held three separate exercises, worried that the approaching drone force would be spotted and attacked before it even closed with the Russian defenders:

To do this right, they would have to invent a new playbook entirely. After all, it was a completely novel approach to an assault. As part of the planning, they established checkpoints, routes and designated communications channels.

And it was more than the attacking air and ground drones:

The mission itself involved complex logistics and communications requirements. No drone swarm technology was used, which meant that each individual drone was piloted by an individual pilot.

Coordinating the ground and air elements was key:

What we do know is that ground and aerial drones were working together, with pilots spaced out in different locations, coordinating the mission while watching the battlefield context simultaneously from a common video feed.

Of course, relying on enemy ignorance and passivity isn’t ideal:

Because of the significant amounts of ordinance being deployed with the ground drones, an early Russian counter-attack could cause the kamikaze drones to explode and destroy the rest of the assault elements.

And that ignorance and passivity wasn’t restricted to the movement across the No-Man’s Land:

Forty-eight hours before the mission began, drones began being moved to their starting points. Success was defined in the mission planning as all drones arriving on target and striking their designated assignments.

The force was small, but unique in the war thus far:

Less than 100 soldiers were involved in the operation, including pilots, logisticians, planners and support staff – all to launch an assault of around 30 drones, ‘Mathematician’ said.

About a half a dozen kamikaze and machine-gun-mounted ground drones were used. Also involved in the assault were several FPVs, including one with a mounted assault rifle. Large copter drones dropped munitions, while dozens more surveillance/recon drones provided battlefield awareness.

The battle itself was brief:

What took days to plan took just one or two hours to play out, along a heavily-fortified Russian position near a large forest.

The attack took the Russians by surprise, causing fear and chaos over the novel “robot” attack. The Ukrainians did not lose control of their drones due to enemy electronic countermeasures.

Yet despite knowing the ground, the ground was a big problem:

Terrain, it turned out, was a major challenge. Ukrainian mud is famous for its thick, sticky texture. The black 'chernozem' soil has been the source of the country's ultra-productive agricultural sector, but also causes incredible challenges for cars, tanks and ground drones alike.

The attack was successful as far as it went. The Russian position was taken without the need to risk Ukrainian troops: “right after the ground drones finished their mission, infantry rushed into the area and secured the positions.”

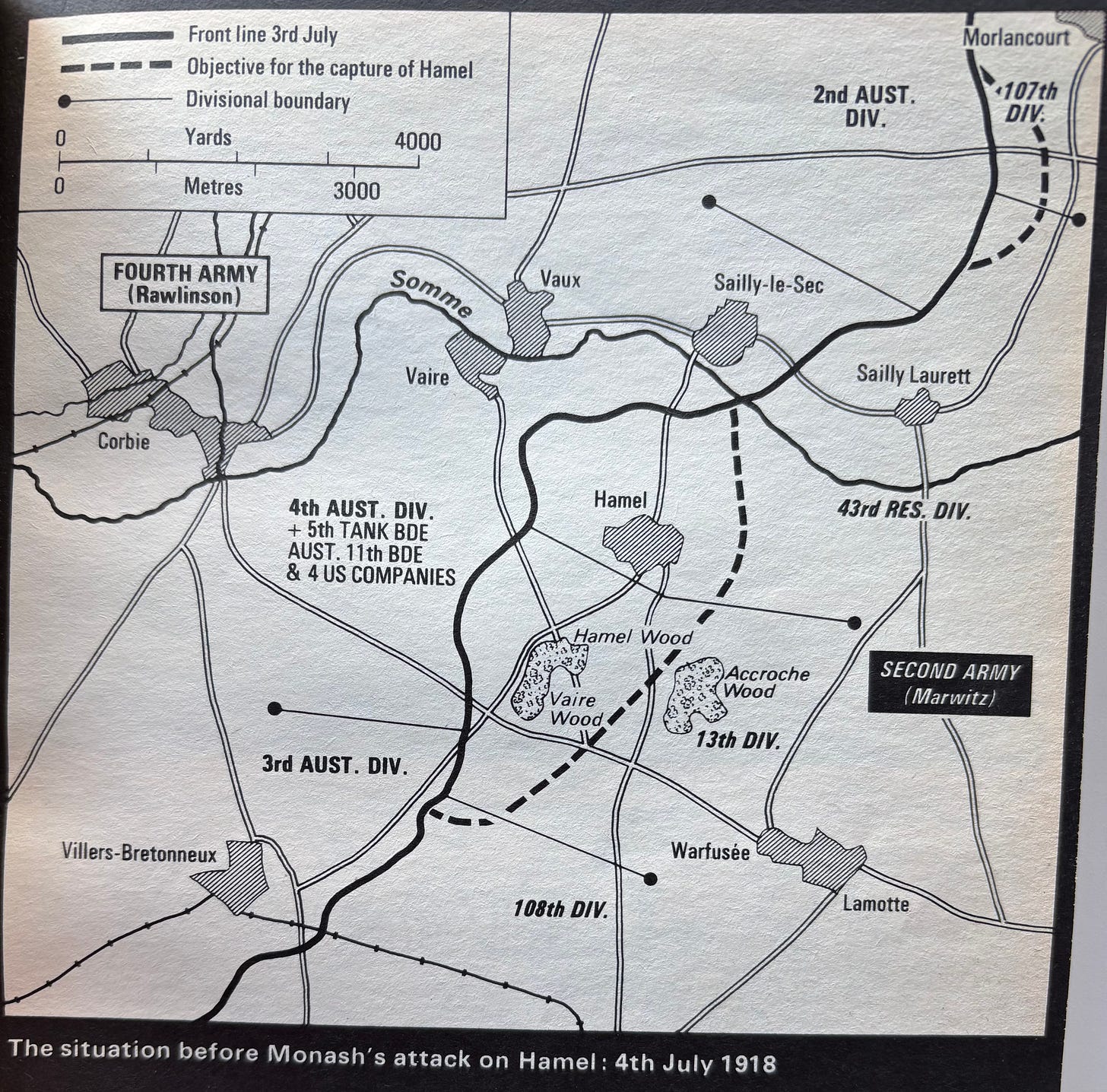

But it went nowhere, really. One can go back to World War I to see the first attempts to figure out the tactics to use the new weapons being developed to break the stalemate on the Western Front. The battle was the July 4, 1918 Australian-led attack on German-occupied Hamel and a nearby forest on the Western Front.*

By June 1918, Germany’s spring offensive in the West had gained a good deal of ground but culminated without breaking the Allied armies. The British wanted to attack both to bolster their own army’s morale with a victory and to test German morale after their exertion. The Australian Corps under lieutenant general John Monash was given the mission. He brought an attitude that led him to embrace the tank, newly introduced in the war to break the bloody defense-dominated Western Front:

I had formed the theory that the true role of the infantry was not to expend itself upon heroic physical effort, nor to wither away under merciless machine gun fire, nor to impale itself to pieces in hostile enganglements: but, on the contrary, to advance under the maximum possible array of mechanical resources, in the form of guns, machine guns, tanks, mortars and aeroplanes: to advance with as little impediment as possible to be relieved as far as possible of the obligation to fight their way forward: to march, resolutely, regardless of the din and tumult of battle, to the appointed goal: and there to hold and defend the territory gained: and to gather in the form of prisoners, guns and stores, the fruits of victory …

Although this edges close to past claims that firepower in different forms could reduce the role of infantry to occupying empty territory after an enemy is destroyed or sent into flight, under the circumstances of the war, wanting that is understandable.

Monash chose as his objective a ridge with the shattered village of Hamel and the nearby forested area on it. He wanted it to be a tank operation. His 4th infantry Division selected as the main element had unfortunately suffered in a 1917 attack that was poorly supported by tanks. The men of the division “loathed and distrusted tanks.”

British 5th Tank Brigade with 60 new and improved Mark V tanks would lead the attack. The 4th division’s 7,500 infantry plus a brigade of the 3rd Austalian Division and four companies of the American 33rd Division were the ground components. The 6,000 assault troops would attack on a front of 6,000 yards, 3-5 times the front that many troops would normally attack on. The 600 guns in support were about half the usual support for such an attack.

Two airplane squadrons were dedicated to support the attack, one earmarked for the infantry and one for the tank brigade. Several others were used during the battle, including one for dropping ammunition to the advancing units. Units had cloth signal markers to identify drop zones to the pilots. In addition, four cargo tanks would carry barbed wire, water, and mortar bombs.

Tank-infantry exercises were conducted. A preparatory barrage would be used because the infantry demanded it rather than trust the tanks to provide fire support with direct fire. The battle plans were explained down to the platoons and sections. NCOs received marked up aerial photos of the target area. And all troops had a map of the area with a message form on the back.

The assault itself was scheduled to go over the top at 3:10 a.m. on July 4, 1918 against a German force of mixed quality. They had some anti-tank rifles. There was just one trench line plus strongpoints in Hamel and the nearby forest. There was not much barbed wire set out.

At 10:30 p.m. on the 3rd, the tanks began to move up to the front from their positions a mile behind the front. The attackers laid out tape to guide the tanks to the infantry battalions and, when the attack began, into No-Man’s land through friendly lines. The tanks moved at half-throttle to reduce noise signature. And bombers flew over the area, dropping bombs on German rear areas to drown out the noise of the tanks. Artillery harassing fire, as usual, commenced prior to the attack, to keep up the routine. This too drowned out tank noises and other preparations.

At 3:10 the preparatory barrage began, largely aimed by maps to maintain surprise. There was some friendly fire on the assault infantry as a result. But smoke from the artillery in the darkness broke apart tank-infantry coordination, resulting in more Allied casualties. But when the light of dawn appeared, coordination was restored, and they moved together. Infantry would direct tanks to deal with German points of resistance. The attack rapidly punched through the German line and reached their objectives in under two hours. Allied casualties were relatively light, including only five tanks lost.

Infantry mopped up scattered resistance and consolidated their gains, aided by the supply tanks that delivered barbed wire, picquets to anchor the wire in the ground, mortar bombs, corrugated iron sheets, 10,000 small arms rounds, 100 gallons of water, and some whiskey. The tanks delivered what 1,200 porters could have moved. The planes dropped 93 boxes of machine gun ammunition to the forward crews.

After this small battle, larger assaults were carried out along the front. And even bigger plans were made for 1919 to both break the trench line and exploit the breach created before enemy reserves could plug the gap and counter-attack.

What will the 2024 methods need to move beyond this small tactical action to achieve operational results?

First, the battle for Hamel was small, but it still dwarfed the tiny Ukrainian attack at Lyptsi. Note that the battles both took no more than a couple hours. But the difference in scale is tremendous, with the Australian test attack about a 100 times larger. And taking much more ground deeper into the German lines.

Both sides practiced their assaults and needed to achieve surprise. Moving the tanks or drones up to the front without being detected were key elements. But note that the British tanks in 1918 were apparently concealed just a mile behind the front. Now, the zone of persistent surveillance extends much farther behind enemy lines just with small drones. Satellites and high flying planes and drones make hiding even more difficult. And sound is not the only way of emitting signals that warn the enemy today.

The Ukrainians worried their small drone assault force would be attacked in the No-Man’s land before they reached their objective. The Australian attack had the numbers to endure initial losses approaching enemy lines and still push on to victory.

The ground condition was a problem for the small Ukrainian ground drones. British tanks were pretty big to move across shell craters and trenches. The Ukrainian attack with small drones could not match that. Just approaching the Russian position was job enough. The British tanks at Hamel were designed to cross trenches. Ukraine will need larger ground drones able to keep moving past Russian trenches to push through the line if this is to be more than a novelty act. Yet larger drones will be easily spotted and destroyed just as crewed armored fighting vehicles near the front are hit.

The Ukrainians were able to consolidate their gain made by ground and air drones with infantry, as Monash hoped to achieve. But again, the scale was tiny.

The lessons from Lyptsi (and hopefully from Hamel) will no doubt shape Ukraine’s plans for a Drone Line to defeat enemies before they reach Ukraine’s manned defensive lines:

The project, dubbed the Drone Line, was announced by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense on Feb 9. According to statements made by Ukrainian Defense Minister Rustem Umerov, it has two core objectives: building a continuous drone reconnaissance capability along the line of defense, and boosting support for and coordination with infantry units to create a kind buffer strip where no troops can move undetected.

Will this initiative stop the Russians cold? Will it be adapted for offensive operations? Could it defend whatever ceasefire line is finally established somewhere between the current front and Ukraine’s pre-2014 invasion borders?

The Allies did not move beyond their 1918 offensive capabilities. Progress on testing tactics and equipment in the war was not made. Indeed, combined arms using tanks went backwards in Britain and France during the inter-war years. It was the Germans who were the first to use new tactics for exploiting the capabilities of these new weapons to create movement on the battlefield and achieve operational results in their opening campaigns against Poland, France, and the Soviet Union. With a side show in North Africa. Poland and France were small enough theaters for the victorious initial campaigns to achieve operational results and win the wars against those nations.

With work and some luck, Ukraine might be able to achieve decisive results by developing and scaling up their Lyptsi attack methods to liberate large chunks of territory captured by Russia since 2014, including Crimea.

Will the West make progress in learning the lessons of Lyptsi? Or will our enemies do so first?

*Section and map on the Hamel attack from Douglas Orgill, Armoured Onslaught (1972).

NOTE: I made the image with the Substack capability.