The Army Role in Asia

Wellington went ashore in the Iberian Peninsula to seriously hurt Napoleon

I am concerned that the Army has decided to accept a minor supporting role in the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOOPACOM) Area of Responsibility (AOR). If the Army simply seeks to sink ships and shoot down enemy aircraft, those in charge of the Pentagon will rightly wonder if the Navy and Air Force should get the resources that the Army is currently using to create those capabilities. If the Army doesn’t see a role for itself carrying out its core competency—large-scale ground combat operations—other services won’t make that argument and the Pentagon and civilian leadership won’t care either.

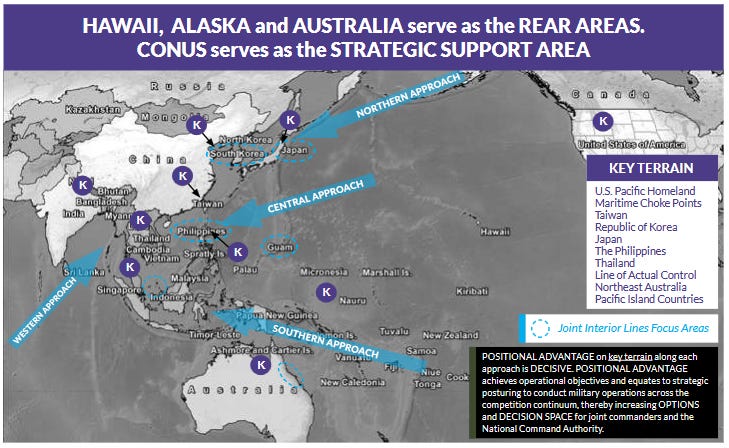

United States Army Pacific sets out its strategy:

Despite widely held bias rooted in a misconception that the Indo-Pacific is an air and maritime theater, the Chinese Communist Party cannot achieve its “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” absent seizing land objectives – the central prize being Taiwan. The long-term competition is a struggle over key terrain – including its human, physical, and information dimensions. Controlling terrain awards control over people, resources, and access to markets; only then could the CCP exert autonomy in the air and maritime commons.

This is encouraging, too:

The Indo-Pacific is the most consequential region in modern history. It is the 21st Century’s geostrategic center of gravity and epicenter of geopolitics, according to national strategic guidance. Many ask what the U.S. Army does in a theater seemingly defined by sea and air, but this question overlooks the fact that 25% of the world’s land areas are in the Indo-Pacific. South Asia is comprised of 10 countries inhabited by 2 billion people, including the most populous country on the planet. Southeast Asia’s archipelagos form a land bridge between the continents of Asia and Australia. Tens of thousands of islands form the Pacific Island Countries throughout Oceania, while many of the world’s largest armies are found in Northeast Asia. The region features the most rugged, distributed, and diverse terrain on the planet – from tropical rainforests and low-lying coral atolls to arctic plateaus and immense mountain ranges.

That sounds good. But I Corps has a more limited notion of operating in that theater with so much land, people, and ground power:

The geography of the INDOPACOM AOR exacerbates posturing corps enabling brigade forces and the corps reserve. This geography typically requires a noncontiguous AO with noncontiguous corps rear areas to enable operational reach. The corps often needs to split enabling brigade forces among multiple geographic locations. It is difficult to relocate those forces within operationally relevant timelines, and repositioning typically involves reliance on the U.S. Air Force or the U.S. Navy.

I’m not saying this isn’t necessary for the section of INDOPACOM from Japan to the Philippines. But that isn’t enough of an operating horizon in such a vast theater with the geography that United States Army Pacific describes.

Basically, I worry that the Army is diluting its energy so much for the sea and air domains that it won’t be the master of its own domain. I keep reading about Army efforts in the Pacific region that neglect large-scale ground combat operations.

U.S. Army Pacific is strengthening its multi-domain capabilities to support joint operations in the Indo-Pacific region. By increasing the scale and frequency of campaigning activities, namely regional exercises that involve long-range fires systems, the Army aims to bolster Allies’ and the joint force’s abilities to counter maritime and air threats. This approach, developed through the U.S. Army’s multi-domain operations doctrine and implemented by newly formed Multi-Domain Task Forces (MDTFs), integrates land-based offensive and defensive capabilities with space, cyber, electronic warfare, and information operations.

Ah, multi-domain improvements. But the domains the Army is focused on jarringly fail to address the land domain. That’s the domain the Army is uniquely capable of fighting in. But instead the Army is just one more Navy auxiliary. The Marines didn’t want to be the “second Army” and apparently the Army isn’t interested in being the first:

Alongside Marine Corps stand-in forces and U.S. special operations forces, Army forces can help secure key terrain in maritime Asia. Land force integration is essential to preventing war and winning the long-term strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific.

Pardon me for bringing this up, but the vision is to be another land-based anti-ship and air defense force to support the Navy. As the Army joins the parade to assist the services designed to provide air and naval superiority, who dominates the land domain aside from small footprints on “key terrain”?

Even in the limited terms of supporting the Navy, the Army will have problems carrying out its supporting role in INDOPACOM:

Just weeks ago, a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) sounded the alarm on the Army’s Pacific pivot: only 40 percent of the Army’s watercraft fleet is ready for operations in the Indo-Pacific. Should a conflict erupt in the Indo-Pacific, only a handful of the Army’s watercraft fleet—an aging, shrinking, and increasingly overworked force—will be available for theater-wide logistics, leaving both the Army and the rest of the Joint force stranded onshore.

U.S. Army Pacific Commander Gen. Charles Flynn routinely promoted the U.S. Army’s ability to serve as the “linchpin force” in the Indo-Pacific—touting the Army’s unique ability to provide staying power, logistical support, and missile defense for the Navy and Air Force. But with readiness rates like this, the grim reality is that a significant portion of this crucial capability could be immobile and stranded onshore should conflict with China break out.

The logistics role for the Army is clearly vital for all the services. As is missile defense ashore and staying power—which I assume means Army troops holding offshore territory rather than just rephrasing “logistical support” for a third thing. I have long had my doubts about Army Multidomain Task Forces that spend resources on long-range fires doing what the Navy, Air Force, and—under Force Design—the Marines are supposed to do.

And if the Army is simply focusing on being a Navy auxiliary force to help in the Pacific sea control fight rather than emphasizing its core competency of large-scale ground combat operations, this development should not be a shock:

[The] Pentagon would need to search for savings or “bill payers” to surge capabilities required to deter potential Chinese aggression against Taiwan, Okinawa or the Philippines.

“One of the largest bill payers in resourcing the strategy of denial should be the Army,” the report said.

The strategy targets both the Army’s active-duty cohort and the National Guard and calls for deactivation of four Stryker brigades, six infantry brigades and two aviation brigades. …

Overall, Dahmer’s report recommends about $70 billion less annually for the Army, which along with other cuts would give about $40 billion more apiece to the Navy and Air Force.

The realignment he calls for in the report would also exact a heavy toll on the security structures that Europe has been relying on for over a decade. For one thing, the U.S. European Command mission would be slashed.

Aside from my multi-faceted alarm about risking Europe by reducing American leadership in NATO, even INDOPACOM which has large expanses of ocean, has a lot of land. I believe there is a synergy from each service dominating its own domain, as I described in this Land Warfare Paper. And I advocated, in Military Review, for the Army adding its core competency to the INDOPACOM region to pose threats to China in all of the domains, in cooperation with allied armies. That will prevent China from focusing on a aero-naval campaign by making it unnecessary to dilute its limited funding to cope with the possibility it might have to fight the Army on land.

How much more difficult would a Chinese invasion of Taiwan be if China knew it could face an American corps on the island? How much would Taiwanese resolve to fight increase knowing that kind of cavalry is on the way?

Mind you, I understand that the Army has to focus on logistics first. The Army is actually required to provide the logistics backbone for other services in addition to its own requirements. So one can’t put the cart before the horse. But it is rare to see any discussion of an Army large-scale combat role in Asia. Perhaps that discussion is premature until the Navy and logistics are in better shape to avoid stranding an Army corps and risking its destruction.

Not that I want to fight a land war in Asia. But I don’t want China to believe it doesn’t need to worry about a land campaign in Asia. I remain concerned that America doesn’t see the Army as anything more than a supporting player in INDOPACOM that never needs to carry out its core competency—large-scale combat operations—in a war with even our pacing threat, China.

Maybe America and its allies can enforce a blockade against Chinese naval opposition and superior shipbuilding capacity.

Maybe China can’t build trade routes inland sufficiently to reduce the impact of a sea blockade.

Maybe our allies very close to China can endure the economic pain that China can inflict on their own overseas trade without breaking ranks.

Maybe our allies within reach of Chinese land and air power won’t be crushed and looted to buy time for China.

Maybe a blockade can work in time and do that in a way that doesn’t threaten the Chinese Communist Party’s hold on political power enough for the CCP to use nuclear weapons.

But that’s a lot of conditional achievements to make a blockade our primary response to Chinese aggression.

Ground power remains vital even in the Pacific region. At the very least, having the ability to land an American Army corps on the Asian mainland in INDOPACOM will pose additional demands on China’s defense efforts that will reduce their ability to break a blockade.

NOTE: Map from the initial Theater Army Strategy document.